La guerra ha terminado. La sociedad inglesa recupera poco a poco la normalidad. Estamos a principios de los 60. John Lewis, en su despacho de Londres, trabaja en un encargo para la editorial Studio Vista. La misión: acercar a la sociedad disciplinas complejas como son el arte, diseño y arquitectura. La solución: lanzar una serie de manuales iniciáticos dirigidos al gran público.

Lewis empieza a tomar decisiones. Los libros no deben intimidar. Serán baratos (tapa blanda), breves (menos de cien páginas), inteligibles (sin lenguaje enrevesado), fáciles de conseguir (buena distribución). Atractivos. Entretenidos. Optimistas pero realistas. Con el deber de enseñar muy bien el concepto que traten. Han de ser atemporales y a la vez cápsula de su propio tiempo.

Encontrar quien los escriba resulta lo más arduo. Sin buenos autores todo será un fracaso. Lewis persuade a nombres consagrados pero también quiere dar voz a talentos emergentes.

La serie es un éxito. Centenares de miles de copias vendidas. La métrica más importante: influenciaron y enseñaron a toda una generación.

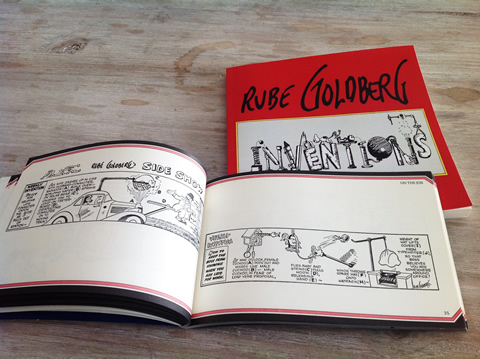

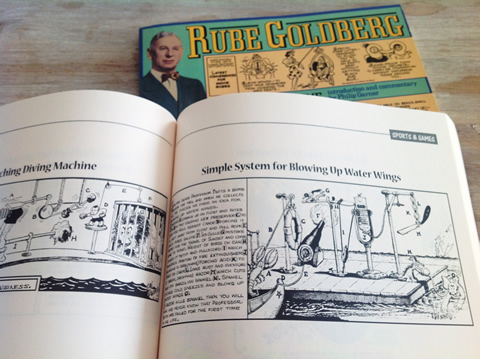

Graphic design: visual comparisons forma parte de la serie. Se publicó en 1963.

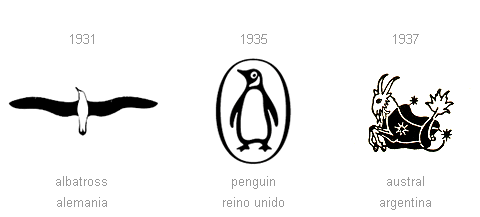

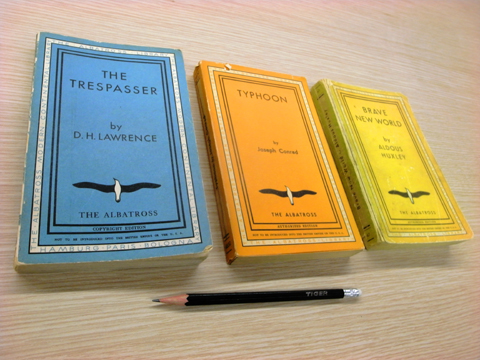

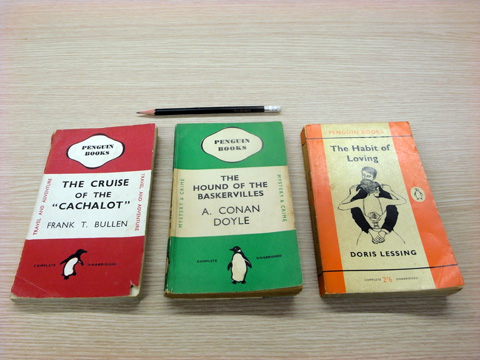

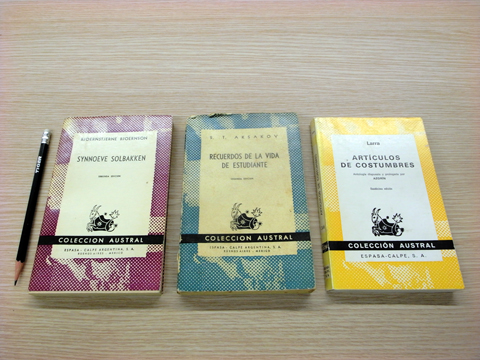

Lewis se lo encargó a unos entonces semi desconocidos Alan Fletcher, Colin Forbes y Bob Gill. Los tres tenían una modesta oficina y empezaban a despuntar con trabajos para Pirelli, Penguin Books u Olivetti. En los 70 fundarían uno de los estudios de diseño más importantes e influyentes de la historia, Pentagram. Sus valores, cincuenta años después, siguen intactos: Una cooperativa más que una empresa, donde los socios se encargan de ejecutar personalmente los proyectos y tratar con los clientes. Es el único estudio de su tamaño e importancia que aún sigue independiente. Resulta inaudito en estos tiempos convulsos de adquisiciones y fusiones.

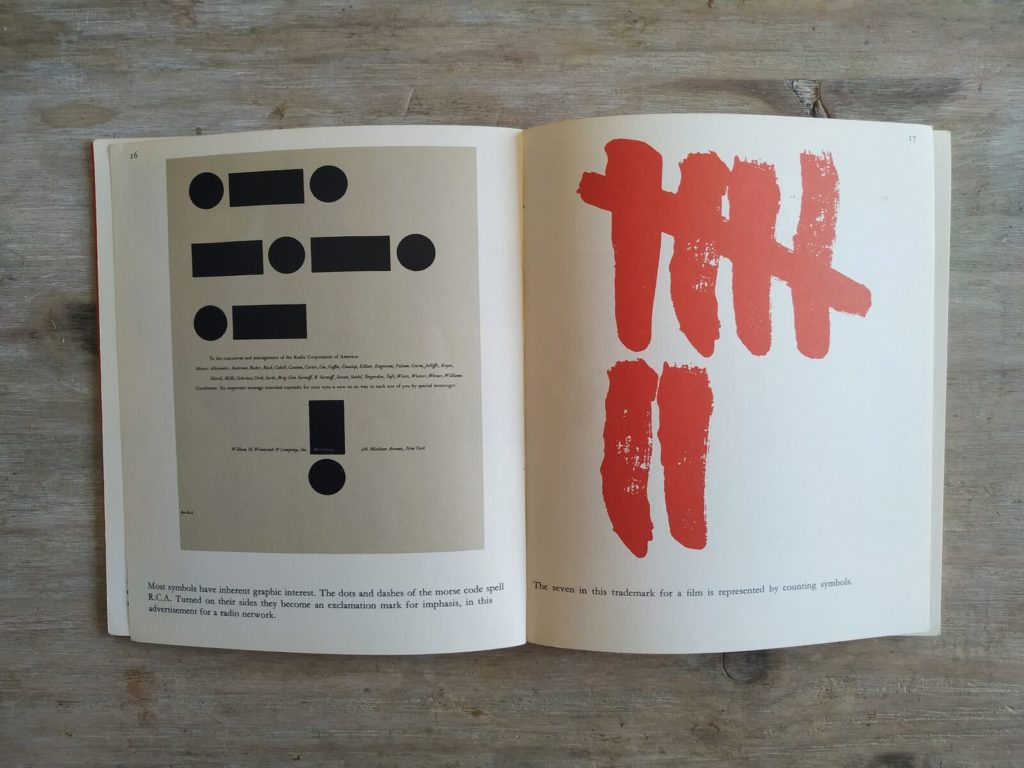

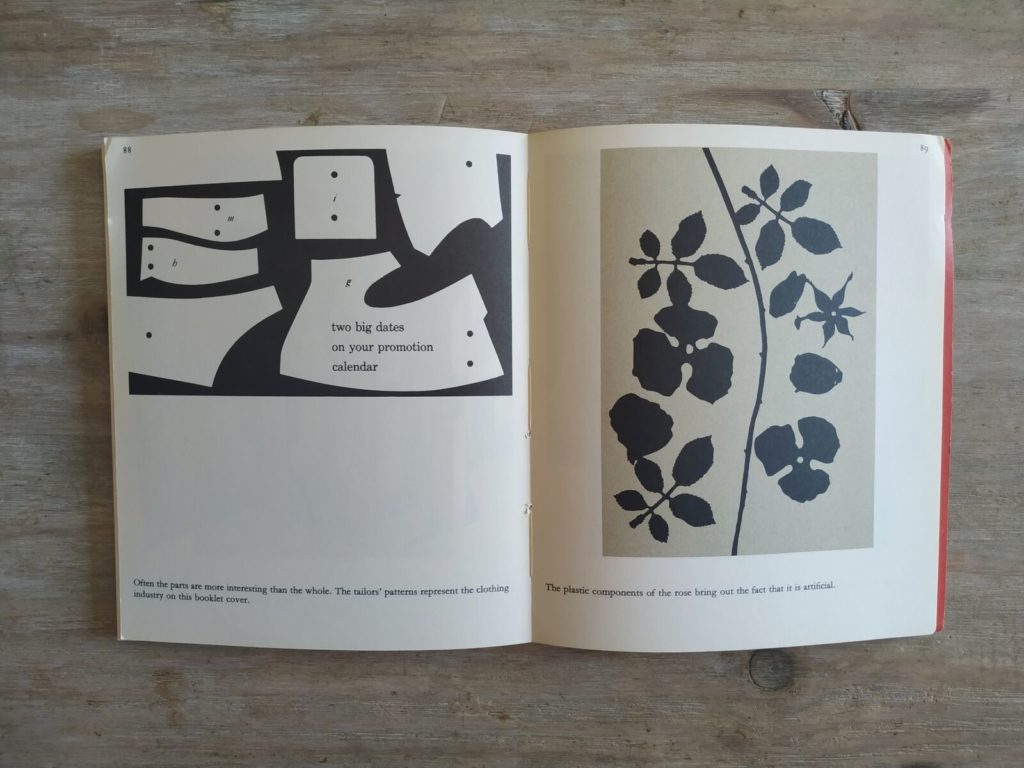

Confrontando trabajos de los mejores diseñadores del momento, de manera magistral, trataban de defender una tesis que es el hilo conductor. Dado un problema, este tiene infinitas soluciones y muchas de ellas son válidas. No hay una única manera de resolver las cosas. El secreto está en el corazón del problema. Un diseñador ha de ser libre y no estar sujeto a modas, reglas o técnicas.

El prefacio que abre el libro, es uno de los más bellos textos que yo haya leído sobre diseñar. Es absolutamente atemporal. Una clase magistral. Aplicable a cualquier actividad creativa. Cumple con todo lo que Lewis pidió. Es imposible decir más en menos.

Me he tomado la molestia de copiarlo. Merece ser leído despacio.

We were asked to write a book on graphics, but unfortunately we are not writers. We felt we could best express our opinions with illustrations than theory.

The vast majority of advertisements, posters, television commercials, booklets and other printed matter clutter our environment and insult our intelligence.

And besides, they are so monumentally boring.

There are, however, some designers even clients who insist that the public deserve and will respond to much higher standards in graphic. They are convinced, as Charlie Chaplin was convinced, that the best way to entertain the public is first to entertain oneself.

Our thesis is that any one visual problem has an infinite number of solutions; that many of them are valid; that solutions ought to derive from the subject matter; that the designer should therefore have no preconceived graphic style.

To demonstrate this we have selected a number of solutions to advertising and communication problems that are efficient and imaginative.

We have paired contrasting or complementary solutions to similar problems; we hope that these juxtapositions will stimulate students and professionals, if only to disagree with them.

Several considerations have limited our selection. Designs which required a large format, or used specific colour not available in this book, or those which were technically difficult to reproduce, had to omitted. We also had to eliminate many brilliant examples for which we could not find an opposite number. With few exceptions we have chosen recent work so that this book will also reflect the climate of the sixties.

The credits, which are listed at the end of the book, presented a problem. One tends to give either too much or too little information in a project of this kind. We have given credits to the problem, to the individual or individuals who actually solved the problem, and to the client.

The designers represented in this collection do not belong to any one school. They work in America, France, Germany, Holland, Iceland, Italy, Poland, Sweden, Switzerland and the United Kingdom. They do have, however, some ideas in common.

Although most of them have done well in their profession, they believe that design is not a business but a way of life.

Unlike painters who should have a personal handwriting, designers are often anonymous, but their work still achieves a vivid personality. Their identity is maintained by a consistently high standard of problem solving rather than by a consistent technique or style.

Of course there are always some impossible clients, but they know that the ultimate responsibility for a bad job rests with the designer and not with the client, however hardheaded and obstreperous. After all, they reason, there are many ways to solve a graphic problem. If one solution is rejected, another must be found.

Each job they do represents a search for new methods of making ideas and images come alive on the printed page; they have enquiring minds and they are not afraid to make mistakes.

They know their craft and use the technology of the graphic arts creatively, rather than be subdued by it. But above all, they never limit themselves to current tastes, or to formal rules of layout, typography and colour.

London, 1963.

Bola extra: Cualquier libro de la serie merece la pena. Todos son maravillosos. Todos tienen prefacios igual de buenos también. Si te topas con uno, cómpralo sin dudar si te va a gustar o no.

Por citar solo algunos: Typography: basic principles (John Lewis), Graphics handbook (Ken Garland), Architecture: a landscape (Peter Cook), Signs in action (James Sutton), Television Graphics (Roy Laughton)…..

Alan Fletcher falleció en 2006, dejando un inmenso legado.

Colin Forbes vive. Hasta donde yo sé, está retirado.

Bob Gill, nonagenario, sigue en activo. Siempre he admirado estas carreras tan longevas. Escribe y da conferencias. Esta entrevista de 2015 en It’s nice that es una buena prueba. (Incluye fotos de su espacio de trabajo).

A finales de verano tuve el inmenso privilegio de entrevistar a Dieter Rams en su casa de Kronberg. El

A finales de verano tuve el inmenso privilegio de entrevistar a Dieter Rams en su casa de Kronberg. El